After twenty years, the famous Maestro João Carlos Martins is finally able to play piano again, thanks to modern technology. In his case, it was a pair of bionic gloves that helped his fingers tickle the ivories after such a long break. What hindered his playing was focal dystonia, the loss of control over long-practiced fine motor movements. It is a common illness of professional musicians. In celebration of Maestro Martins’ comeback concert, we talked with Prof. Dr. Eckart Altenmüller about how his research resulted in today’s treatment of focal dystonia, his thoughts on bionic gloves, and what composer Robert Schumann and Maestro Martins have in common.

What is focal dystonia, also often called musician dystonia?

Focal dystonia is the loss of control over long-practiced fine motor movements. The term ‘focal’ means that it usually affects only one limb, for example, the left or the right hand; and dystonia means abnormal muscle movement. For musicians it often occurs at the peak of their career, when arbitrary movements such as fine coordinated movements on the instrument are disturbed.

How do you get the disease?

There is a strong connection with the length of practicing time: how much time and how many years you spent practicing, repeating the same movements over and over. Other risk factors are, for example, a history of chronic pain, starting late in life with practicing, or genetic factors such as family members who suffer from Parkinson’s or something similar.

Is there a cure?

This is a learned disease that can be unlearned. It is a matter of disturbed neuronal networks. They are malleable, they are adaptable. Although the movements are different after recovering from dystonia, the symptoms can be alleviated and you can modify your repertoire in such a way that you can still make music at the highest level. This is part of the rehabilitation process.

For Maestro Martins help came in form of bionic gloves. They helped him play again. How do they work?

There are two effects. The first is the so-called sensory trick. All movements are tied to feelings in the hand. If I change the feelings in the hand, I usually change the movement for the better. The second effect is that the gloves can counteract the cramping tendency and the involuntary retraction of fingers, in addition to relieving the muscles of the forearm.

Bionic gloves have two effects – the sensory trick and counteracting the cramping tendency. (photo credit: Jean-Claude Kuner)

So bionic gloves are doing the magic trick?

No, they are still being developed. They are not yet able to handle highly complex, very fast finger movements like trilling accurately down to the millisecond. It has brought Maestro Martins a certain relief, but you can see clearly that he does not have his former virtuosity.

So why are the bionic gloves from Maestro Martins are getting so much attention?

Maestro Martins has a very honorable motivation in promoting his story. He wants to improve the lives of professional musicians. Focal dystonia is the most frequent occupational hazard for musicians. And even today there is a need to make this disease known.

What do you mean by that?

The diagnosis for focal dystonia has only been known since 1992. Back then, it was very unexplored and most of the affected musicians experienced a years-long journey similar to João Carlos Martins. And although we are able to diagnose focal dystonia a lot earlier and better today, we have more to learn about prevention methods such as healthy practicing and good self-management. Today, the focus needs to lie more acutely on the psychological consequences of a musician’s dystonia.

Can you explain that in more detail?

All of our motor activity is a constant expression of our emotions and an expression of our psyche. If I have a very rigid mind, then my musculature automatically becomes rigid. The pressure musicians are under nowadays is much greater than in the past. Paganini just went on stage and played what he enjoyed. Today we have 20 reference recordings for comparison. So, our therapeutic measures are also geared toward relieving the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse coming with musician’s dystonia: the anger that you are practicing and it is not getting better, the shame that colleagues do not understand your problem, the guilt that you have overworked yourself, and the fear about whether you can continue your profession at all.

How does it feel to see how your research results are translated into practice?

For me it is a great success, a very satisfying activity. I have been at the Institute in Hannover for 28 years doing this musician clinic/consultation with a focus on dystonia. Since then, I have treated over 2,000 patients. And today we are in a position to offer so many therapeutic options, which we have developed over the last 30 years. It’s a great feeling for me.

Thanks to bionic gloves Maestro Martins is able to play piano again. (photo credit: Jean-Claude Kuner)

How would you have helped Maestro Martins?

The standard treatment is to start with retraining. Retraining means that you learn to perform the movements correctly again. This includes putting obsessive behavior into perspective. Freeing the patients from the pressure to succeed. In addition, there are currently two medications that work very well on dystonia.

The wrong movements in his hands I could have treated with a carefully dosed local injection of botulinum toxin, so that he no longer cramps his fingers, but still has enough strength to strike the piano keys. And finally, and maybe most importantly, I would have encouraged him to move to composing and conducting much earlier and make himself less dependent on his hands.

Why is finding new ways as a musician so important?

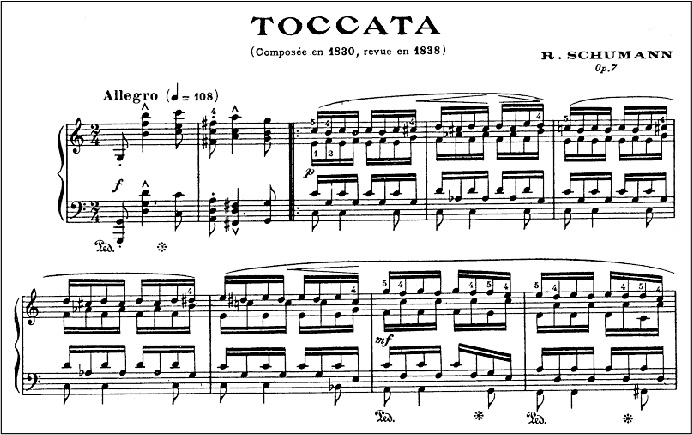

He has the best example before his eyes: Robert Schumann, who also suffered from focal dystonia. Imagine if I had treated Robert Schumann. That would have been a disaster. He would have become one of the nameless, Romantic piano virtuosos that no one knows today. Now, fortunately, he is one of the greatest Romantic composers of his day.

Would Schumann have jumped at the chance to wear bionic gloves?

No, not at all. In a letter to his mother, he wrote “Don’t worry about my fingers. I can compose without them, and I wouldn’t have been suitable for a traveling virtuoso in the first place.” He had very good self-awareness. And I think that’s the task for all of us – that we find solutions with the resources we have available and adapt if necessary. And if I am a very musical person, then I can develop and refine musical skills without my hands and pass them on to others.

Prof. Dr. Eckart Altenmüller is Full Professor and Head of the Department of Music-Physiology and Musician’s Medicine at the University for Music Drama, and Media, Hannover since 1994 and a leading expert on the topic of focal dystonia. His research focus is on brain processing of music and motor learning in musicians. If you are interested in more details regarding Schumann and focal dystonia, have a look at his book chapter “Robert Schumann’s Focal Dystonia” written by Prof. Altenmüller. You may also be interested in our article collection about dystonia.

Comments

Share your opinion with us and leave a comment below!